Walter Lindenmann (1993, p.9), an experienced public relations practitioner claims that the evaluation of public relations programmes and activities requires a mix of techniques: “it is important to recognise that there is no one simple method of measuring PR effectiveness. Depending on which level of measurement is required, an array of different tools and techniques is needed to properly assess PR impact.” This article discusses two evaluation models and one evaluation process: preparation, implementation and impact model (PII); Macnamara’s pyramid model; and CIPR’s five-step circular planning, research and evaluation process.

Preparation, Implementation, Impact (PII)

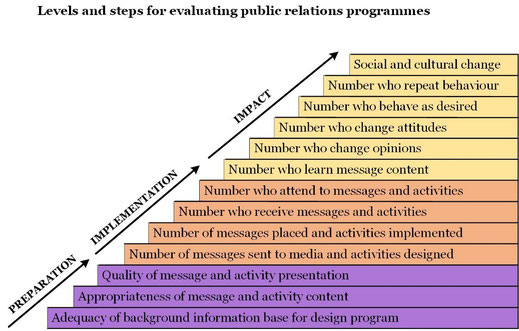

Cutlip, Center and Broom (2013, p.343) developed a three-level evaluation model for differing demands: preparation, implementation and impact (Figure 3). According to the authors, “evaluation means different things to different practitioners” and thus does not prescribe an exact methodology. Each step in the model is designed to increase understanding and add information for the assessment of effectiveness. The ‘preparation’ level considers whether adequate background information has been collected to plan the programme in an efficient and effective way. Besides, the content of materials is examined to make sure that it matches the designed plan. The quality of message and presentation of materials are also considered.

At the ‘implementation’ level, evaluation takes into account how tactics have been applied. Specifically, the authors examine the distribution of materials, the number of implemented activities, and the number of those who received messages and attended activities. The biggest part of the public relations evaluation is centred around the ‘implementation’ level. However, Broom and Sha (2013, p.348) stress that “the ease with which practitioners can amass large numbers of column inches, broadcast minutes, readers, viewers, attendees, and gross impressions probably accounts for widespread use – and misuse – of evaluations at this level.”

The third level of the model examines the impact of a PR programme, that is the extent to which the outcomes outlined in the objectives for the programme have been achieved. This level requires direct measurement using research techniques, and an understanding of how to employ these techniques as well as a certain level of creativity in establishing indicators for behavioural, social and cultural changes.

Further, authors stress that this model acts as a reminder and checklist when planning evaluation. They also argue that:

“The most common error in program evaluation is substituting measures from one level for those at another level. This is clearly illustrated when practitioners use the number of news releases sent, websites visited or pages viewed, brochures distributed, or meetings held to document alleged programme effectiveness. These are not measures of the changes in target publics’ knowledge, predispositions, and behaviour spelled out in programme objectives. Evaluation researchers refer to this as the ‘substitution game’. Somewhat analogously, magicians talk of ‘misdirecting’ audience attention from what is really happening in order to create illusion” (Broom and Sha, 2013, p.344).

Macnamara's Pyramid Model

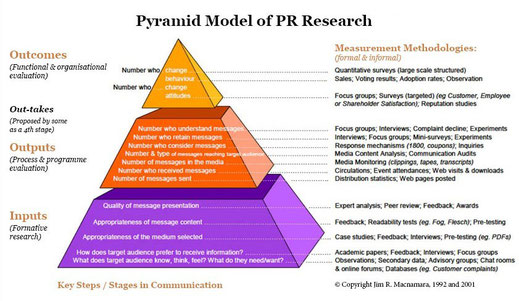

The Pyramid model, created by an Australian evaluation specialist Jim Macnamara (Figure 4), has a bottom-up structure, with the base of the pyramid being the starting point of the strategy and the peak being the outcome of the campaign. According to Macnamara (2005b, p.264):

“The pyramid metaphor is useful in suggesting that, at the base when communication planning begins, practitioners have a large amount of information to assemble and a wide range of options in terms of media and activities. Selection and choices are made to direct certain messages at certain target audiences through certain media, and ultimately, achieve specific defined objectives (the peak of the programme or project).”

Written by Liudmila Kazak

Further, the pyramid consists of three parts: inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Inputs are elements of communication projects and programmes and include the following: the choice of medium, content of communication as well as format. Outputs, in turn, are the materials and activities created (e.g. promotional materials, events, and media publicity) and the process to create them. Outcomes are the impacts and effects of communication efforts. To find out whether the target audience has changed its behaviour or attitude, a number of methodologies can be used – ranging from desktop research to observation and quantitative or qualitative research.

The author also argues that the key processes in the pyramid model have been derived from the PII model and that his model offers and extra value by adding measurement methodologies for each of the three steps (Macnamara, 2005b. p. 266-67). Moreover, to allow data to be integrated into the ongoing monitoring and development of communication programmes and projects, the pyramid model includes formative and summative research methods.

CIPR'S Planning, Research and Evaluation (PRE) Process

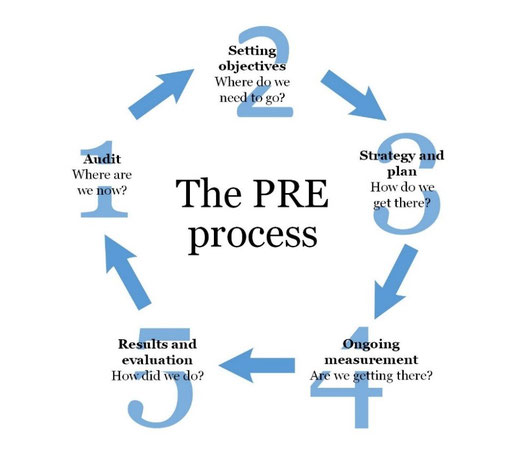

In 2011, the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) published several editions of its Evaluation Toolkit to give PR and communication practitioners practical and efficient tools to undertake evaluation. Experts focused on the concept of planning, research and evaluation, which positions evaluation as an integral part of public relations campaign and stresses a close link between evaluation and research (Figure 5). The CIPR’s (2011, p.9) proposed scheme is a dynamic and iterative process that consists of five steps: audit, setting objectives, strategy and plan, ongoing measurement, and results and evaluation.

The first step in the process is concerned with doing research and gathering information to form a base on which the campaign or programme is based. The SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely) objectives, which are also aligned with the overall business goals, are set during the second step. The third step deals with the strategy and its implementation. Besides, during this stage practitioners should decide upon the type of measurement to be used and pre-test PR techniques and messages to be deployed. Further, the fourth step deals with the ongoing measurement when checks are made and adjustments are introduced, if necessary. The fifth step deals with the examination whether and to what extent the set objectives for the campaign or programme have been achieved.

In conclusion, Walter Lindenmann's insight from 1993 remains relevant today, emphasizing the complexity of evaluating public relations effectiveness. As he rightly stated, there is no one-size-fits-all method for measuring the impact of public relations programs. The discussion of two evaluation models, the Preparation, Implementation, and Impact Model (PII), Macnamara's Pyramid Model, and the Chartered Institute of Public Relations' (CIPR) five-step circular planning, research, and evaluation process underscores the diverse array of tools and techniques needed to comprehensively assess public relations impact. This reinforces the dynamic nature of the field, requiring practitioners to tailor their evaluation strategies based on the specific objectives and levels of measurement required.

Bibliography:

Broom, G M and Sha, B., 2013. Cutlip and Center’s Effective Public Relations, 11th edn, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliff, NJ.

Bryman, A & Bell, E., 2015. Business Research Methods, 4th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CIPR, 2011. Evaluation toolkit. [online] Available from: https://www.cipr.co.uk/sites/default/files/Non-member%20excerpt%202_0.pdf [Accessed 20 May 2018].

Daymon, C & Holloway, I., 2011. Qualitative Research Methods in Public Relations and Marketing Communications, 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

Foster, J., 2012. Writing Skills for Public Relations, 5th edition. London: Kogan Page.

Gregory, A., 2015. Planning and Managing Public Relations Campaigns, 4th edition. London: Kogan Page.

Hon, L. & Grunig, J.E., 1999. Guidelines for measuring relationships in Public relations, Institute for Public Relations [online]. Available from: https://www.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines_Measuring_Relationships.pdf [Accessed 23 May 2018]

Lindenmann, W., 1993. An ‘Effectiveness Yardstick to measure public relations success, Public Relations quarterly, 38 (1), 7-9.

Macnamara, J. R., 2005b. Jim Macnamara’s Public Relations Handbook, Archipelago Press, Sydney.

Newsom, D & Haynes, J., 2011. Public Relations Writing Form & Style, 9th edition. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Noble, P., 1999. Towards an inclusive evaluation methodology, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 4 (1) 14-23.

Parsons, P., 2016. Ethics in Public Relations, 3rd edition. London: Kogan Page.

Smith, D. R., 2016. Becoming a Public Relations Writer: Strategic Writing for Emerging and Established Media, 5th Edition. New York: Routledge.

Tilley, E., 2005. The ethics pyramid: Making ethics unavoidable in the public relations process. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20 (4), 1-11.